Homing practices and the archive

by Tammy Langtry, 2024

Guest contribution by Tammy Langtry for PERSPECTIVES.

Homing practices and the archive

To be invited to enter someone else's archive, the MONSTER ARCHIEF, is to encounter someone else’s memories. A resoundingly personal encounter because it uncovers someone else's truth - the thing they dare not defy or reprimand. They hold themselves to its truth; to defy this archive would be to defy some sense of things before their own time - a time they are also tied to. Some of these things are irrational compulsions to hold - to prove ‘something’ happened, some are ring-fenced things by bureaucracy and there is the archive as proof of things. A pickled preservation, whether it impounds on your present is a question only answered once you open it.

The archive, a system built to honor the maker, in some way the archive can look like any archive of any place: architectural drawings which follow the principles of technical and approved drawings of land, of buildings and of cities. Documentation of the objects and its markings - classification systems based on their materiality and time. Because of this ‘formula’ in its order, the archive of the Colonial Project is a global project, a trickster, implying its duplication, insinuating we all look the same or perhaps to shape everywhere to look like itself.

The mirror in the ground

Traveling through De Mepsche’s ‘Building’ on the Monster Archief website, a constellation or constitution of images, texts, fragments and propositions to remembering the building, to orient ourselves to the site. This accumulation of space and architecture, a positioning of the subject and a delicacy in re-presenting the structure which centralizes the acts of violence – the building never ‘stands still’ – it contorts and appropriates itself for us.

Bylma Assembly v1 by Siem de Boer, Michiel Teeuw, 2023. Animation speculating the development of Borg Bylma through the ages. Longitude: 53°13'48.3"N. Latitude: 6°22'39.0"E.

In this video, Bylma Assembly v1 (2023), we see the many versions/iterations of the house, the ground has little imprint besides a rectangular form with lines to represent the initial buildings. We view it from all sides, white lined sketches of the facade of the house appear and become colored. The house grows an arm to the left – it then grows an arm to the right. It reaches out into the ground before it and creates a U shape. It is encircled by a moat, with a bridge. It all appears as if imagined into being but who is imagining it? Who is drawing it?

The building begins to spin…… or am I running around the building?

The windows glisten.

As the video continues, we see architectural renderings working themselves from a blueprint to a digital rendering, the grounds are landscaped, we look over its birth. And then….. the house disappears - it lowers itself into the ground – did it bury itself?

We are alone, looking at the empty landscape.

This animation, architectural and yet, speculative, brings us closer to the Borg as a building while alluding to a sense of knowing, constructing the Borg in many forms of seeing.

I was disturbed to only find pieces of information about what happened at this Borg. Once foraging and reading through the crimes committed, the house is no longer a house, it is a memory, glistening. The building glistens as a monument to these acts – I wonder what the ground carries with the house's memory.

In the video, we see the ground absorbing the house. As we watch the house disappear, dissolve, I wonder about the gaps and holes. How do we reconcile between the ground it stands on and the memories it left beneath it. When does the ground rest? Or is it constantly holding something?

I write from South Africa, my home country - Cape Town, more specifically. As I look at the Borg Bylma, I think of another Borg or Castle with its own history of horror. Its material history, a memorial to the colonial project of architecture and the ‘birth’ of a ‘new’ type of city in the Cape.

The Castle of Good Hope, was first built in clay in approximately 1650 (not long after an early phase of Borg Bylma was created) - the ocean facing facade was exposed to the sea salt water of the ocean and had begun eroding - this was rebuilt in 1652 using the nearby rock faces (Table Mountain, Lions Head and other nearby and further afield mountains all the way down the tip of the Cape. Unlike archaeological digs which prioritizes what is found in the ground as representations of life, these quarries removed large chunks of limestone, sandstone, marble– to make a new life. To this, ground shells and other natural materials were prepared and baked in a kiln near the Castle. As the Castle infrastructure developed so did the building materials, the Castle was connected to several vantage points along the coastline, spanning out left and right along the shoreline. The materials which defined the colonial ‘taste’ which were not found in this area, were imported - materials from the first world, were shipped in to reproduce the Dutch colonial aesthetic, punctuate the landscape and delineate the seaside as its property. These quarries stand as holes of extraction till today in the mountain side and landscape of the Cape.

What was first a shelter for the United/Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie - a chartered trading company) turned a defense site, turned State infrastructure. Castle’s between Jakarta (then called Batavia or Jayakarta) (1631) and Itamaracá (1631) had already been defined - they stretched out along the map, left and right from the Cape to define the trade route of the VOC.

These transitions from the shelter, to a defense, to a Stately structure - allow this structure to dictate life and impose its functional power. They replicate a Colonial archive, removing life and situating what was built as the central resource.

Mapping Bylma 02 - Bert, by Bert Nijboer, Michiel Teeuw, 2023. Research session with Bert Nijboer about the Borg Bylma. Part of the series Mapping Bylma, which constructs an image of Borg Bylma through various encounters with different kinds of knowledge.

In engaging with the archive, wondering of the extractions and losses of both sites – could the archive in one site follow the same shape and form as the other, could one history meet the other through the Borg? Could a small piece of rock from the Monster Archief reflect and stand in for the gaping holes left in the landscape of the Cape. Does history seep into the ground the same way De Mepsche’s building did? Does the remarkable history experienced in one place find solace in another place? Can the scale of one history be replaced or replicated with another?

“Would the role of the archive be to fill the gap created by this loss of memory?”

To think about these buildings and its extractions and holes, I wondered the degree to which the shadow and inversion of the image, the tracings and removal of the structures highlight the act itself, its memory or the individuals involved.

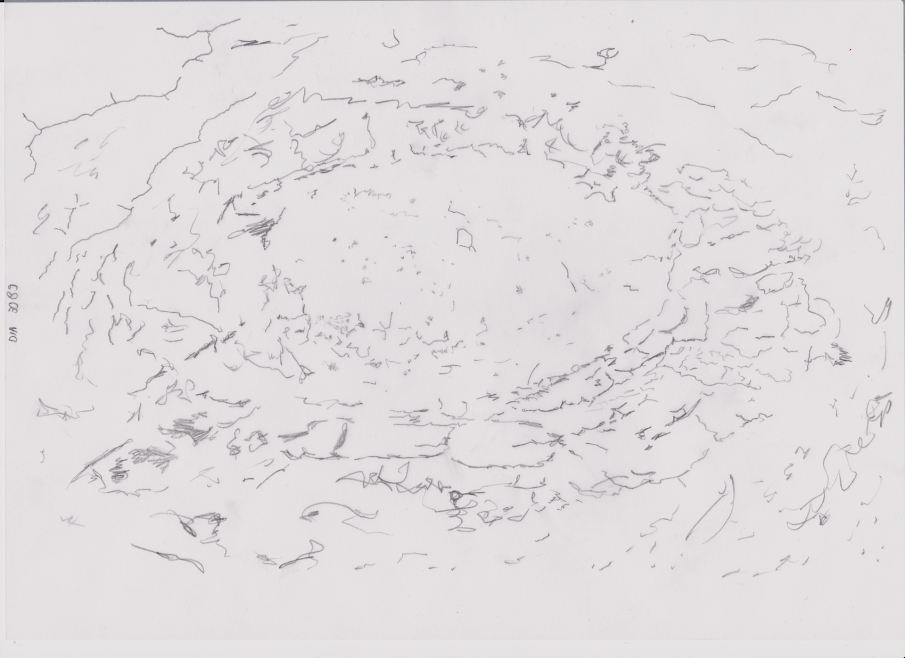

Through its archaeological dig, a series of photographs of the land, the workers and the findings Archief presented rock rubbings (or are these rock imprints?) - they represented the shadow of the rock, the relief of the rock - should the rock be represented by its shape or its markings? Did the site/rock need to be relieved of its memory, of what it was representing?

More than trying to create something ghostly, it allows a way of looking without the grand spectacle of the building - we don’t see the maker (as is often the case in colonial conquest and imposition) but the surface marks and movements which shape the rock. I wondered: How do we archive the emotional landscape of the things we don’t see in the archive?

These archives remind us of the liquid ambiguity of archived information - we are always unstable in them. The frenzied madness of the land we ‘own’ or whose skin we have bled on.

In Impact Studies, work is done to measure the effect something has had on its environment - it asks the question, what has changed or what has it changed.

These unstable monuments (the unfinished and inter-relational) is a critical reorganizing and dusting off the archive to understand its impact and purpose for those using it.

The shadow drawings from the Monster Archief represent other kinds of archaeological material - the material of memory.

When we declare that shadow is a vehicle for what cannot be seen and the start of our journey to another way of seeing.